Undergraduate Experience: Advising, Mentoring, and Development

Undergraduate Experience: Advising, Mentoring, and Development Refinement and Implementation Committee (RIC) 5

Committee Members

Ian Waitz (Chair), Michael Bergren, Rick Binzel, Baptiste Bouvier, DiOnetta Jones Crayton, Anne McCants, Kris Prather, David Randall, Janet Rankin, Mike Short, and Lauren Pouchak (Staff)

Abstract

The RIC 5 report recommends implementing a stronger undergraduate advising structure where students are supported by a group of newly hired professional advisors who work with them from admission to augmenting the work done by faculty advisors in departments. These new “Institute Advisors” will help all students identify and achieve their personal and academic goals while at MIT. The new centralized advising resource will be led by a new Director of Academic Advising.

Thriving is not just about academic performance. While the classroom and lab remain the central arenas of student learning, we must also foster other skills and development in our students if they are to flourish both at and after MIT. An introduction to a broad education, opportunities to expand intellectual horizons, and personal and professional success should be the end goals for students along with the successful completion of the requirements for a diploma. The diverse backgrounds and identities of undergraduate students lead to many different journeys through the Institute. Students arrive with varying previous experiences and levels of knowledge about how to fully access MIT's considerable resources. What is sometimes called "the hidden curriculum" of success needs to be uncovered and made available to every student regardless of their starting point. All should leave MIT with the tools to live healthy and purposeful lives.

Findings

The quality of MIT’s undergraduate advising is far from what it should be. Surveys conducted by Institutional Research consistently demonstrate challenges around advising for MIT students. The Gallup-Purdue Index, a recent survey of more than 30,000 U.S. college graduates, found that graduates with at least one professor who made them excited about learning and cared about them as a person, while also having a mentor that encouraged them to pursue their goals and dreams, have more than double the odds of being engaged at work and thriving in well-being after graduating college. At MIT, 53% of first generation and/or low income (FGLI) students, 47% of underrepresented minority (URM) students, and 43% of students not in these categories could not identify a single faculty member at MIT who they felt had taken a personal interest in their success. Over 30 years of undergraduate advising reports, pilots and memos internal to MIT provide a picture of the changing nature of undergraduate advising needs and the faculty role within it, but show little change to provide the structured support needed to achieve past recommendations. Previous internal reports and memos also nod to the ‘advising network’ available to students at MIT, but for those who do not know how to navigate it, accessing the network and the hidden curriculum can be a challenge. We do not need further study of undergraduate advising at MIT, we need a plan for implementing change.

National best practices provide a framework of support that can benefit all students. NACADA describes describes how effective advising happens when institutions (1) maintain a consensual, documented, university-wide definition of effective advising; (2) establish a clear advising mission based on student learning outcomes; and (3) establish an organizational structure that has a central, senior leader with university-wide responsibility for advising strategy, operations, and assessment. In addition to national best practices, our long-standing First-Year Learning Communities (FLCs) provide MIT-specific knowledge and expertise in the areas of student advising, community building and belonging. The Distinguished Fellowship Office also guides students to a deeper understanding of their intellectual and professional preferences while introducing them to new research or career options through reflection and introspection, but it benefits only a fraction of our students. Both of these programs’ input and guidance are essential elements in the proposed Advising Implementation Plan.

It is clear MIT needs a sustained undergraduate advising structure that supports high-level objectives including the following:

- Equipping students with knowledge about the value of advising and skills to form lasting and mutually beneficial mentoring and advising relationships.

- Guiding students to explore majors, careers, and other intellectual pursuits, balancing early access to departments of interest with encouragement to explore broadly.

- Empowering students to persevere in the face of any academic or social difficulties by identifying and using strategies and resources, seeking feedback, and accepting help and support from others.

- Engaging students in critical reflection on connections between course content, interests, sense of purpose, and personal and professional goals.

- Collaborating with other offices to help build a sense of community for groups that may desire and it, including veteran, FGLI and URM students who may not come to MIT with necessary cultural capital or built-in networks to navigate the Institute.

- Providing appropriate educational resources, best practices and training for members of the MIT community such as staff, faculty, and other instructors who advise in departments, and are primary advisors to undergraduates in their upper-level years.

Recommendation

After reviewing the ideas on advising and mentoring of undergraduate students developed by the Task Force Phase 1 Working Groups on Student Journey (“Finding Your People” and “Finding Your Path”) and Research (on the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program [UROP]), as well as ideas proposed by the First Generation/Low Income Working Group Report, the DEI Strategic Action Plan, and national best practices, the committee strongly recommends implementing a stronger undergraduate advising structure where students are supported by a group of newly hired professional advisors who work with them from admission to graduation, augmenting the work done by faculty advisors in departments. These new “Institute Advisors” will help all students identify and achieve their personal and academic goals while at MIT. The committee’s proposed implementation plan provides a framework for MIT to improve the experience of all undergraduates by incorporating established best practices into the undergraduate advising system.

A long-term commitment and multi-year implementation plan are necessary to create an advising system that works for all undergraduates. The proposed four-year implementation plan is intended to provide a framework which is not overly prescriptive, such that it can evolve as it develops based on continuous assessment. The committee discussed the pros and cons of a speedy launch of this new initiative. We believe getting it right through a deliberate and iterative process is more important than doing it fast. A new director of a centralized advising system that augments and supports department advising will need to understand the complex MIT landscape that includes a varied set of services. A new director will also need to onboard a nucleus of advisors. It is hoped that these advisors will bring their own creative ideas to the planning process and will, in turn, be able to acclimate and train future cohorts of advisors.

A strong, strategically minded leader is needed to ‘conduct the advising orchestra’ of academic advising resources and coordinate the efforts of a new advising center that includes the Office of the First Year (OFY), with those of campus partners that include but are not limited to the Office of Minority Education (OME), Student Support Services (S3), Office of Experiential Learning (OEL) including UROP, Academic Administrators, Undergraduate Officers, the Teaching + Learning Lab (TLL), Residential Education, the First-Year Learning Communities (FLCs), Career Advising and Professional Development (CAPD, including the Distinguished Fellowships Office), and faculty champions. The Advising Center, along with its campus partners will initially need to work to socialize the ideas of this new model across campus, and create community buy-in for the Center. Continued updates to the Committee on the Undergraduate Program (CUP), the Committee on Curricula (COC), and the Committee on Academic Performance (CAP) as the process unfolds are imperative.

The four-year implementation plan, as proposed, does not specifically address the needs of all students immediately. We therefore encourage the new director to identify mechanisms to support upper-level students, particularly those who need it most, by opening up some services to a broader cohort of students if possible and consistent with staffing. These services and supports could include, but are not limited to mentoring meetings, upper-level seminars, and peer programs to supplement advising in departments.

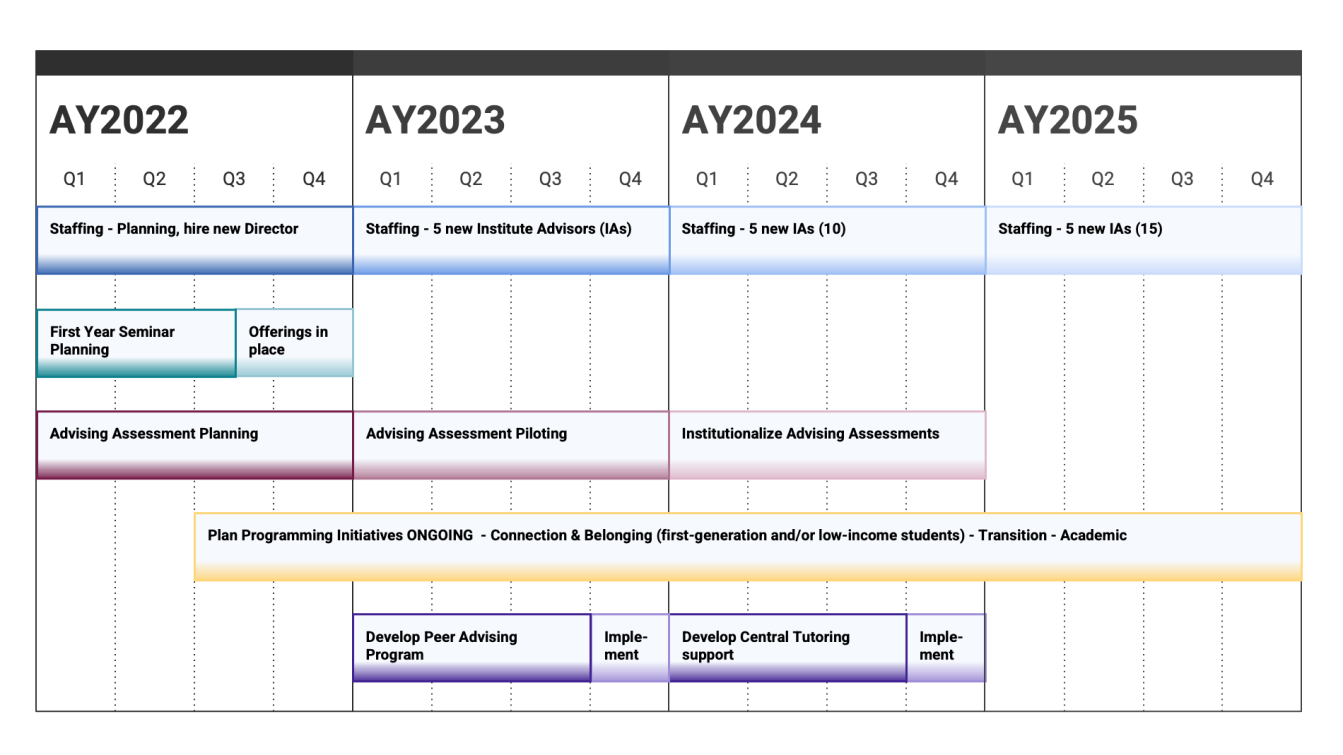

Timetable and Milestones

The recommended implementation plan focuses on five main components: staffing, academic offerings, peer support, assessment, and programming. The phased four-year approach below begins with a planning year and each subsequent year adds staff, peer support, programs and advising assessments that can be adapted and shifted as needed.

Financial Resources

Hiring a new group of Institute Advisors and a Director for a new Advising Center requires a large, ongoing investment. These new staff members will have the important task of working with faculty advisors to guide, empower, engage and support students from matriculation to graduation. By investing in this group of advising professionals to augment our current system, we can create better all-around efficacies and outcomes for faculty, students and staff. In addition to yearly staffing costs, the following budget estimates costs to resource student programming. We expect additional one-time start-up costs to be modest (~$70K).

| Yearly cost estimate: | |

|---|---|

| $171,600 | Advising Center Director ($125,000–$150,000, avg = $171,600 with 24.8% EB) |

| $915,408 | Institute Advisors: 9 at Assistant Dean level ($78,000–$85,000, avg = $101,712 with 24.8% EB) |

| $505,440 | Institute Advisors: 6 at Staff Associate level ($60,000–$75,000, avg = $84,240 with 24.8% EB) |

| $97,344 | Administrative Support: 1 Communications Officer level ($75,000–$80,000, avg = $97,344 with 24.8% EB) |

| $105,350 | Increase in base budget, including professional development for staff |

| $75,000 | Increase in student programming budget |

| $1,870,142 | Total, phased in over four years |