One Agile MIT

One Agile MIT Refinement and Implementation Committee (RIC) 14

Committee Members

Heather Williams (Chair), Olu Brown, Brian Canavan, Glen Comiso, Elizabeth McManus, Nelson Repenning, Lisa Schwallie, Mary Ellen Sinkus, Mark DiVincenzo, Lydia Snover, Mary Roderick (Staff) and Connie Winner (Staff)

Abstract

RIC 14 proposes the creation of a “One Agile Team” that will shepherd strategic improvements to existing business practices and systems as well as providing support to new strategic initiatives. This cross-functional team will coordinate projects and manage the portfolio of potential future projects thus supporting the decision making by senior leadership on administrative improvements across all domains (educational, administrative, and research) at MIT.

Problem Statement

MIT has no overarching home or a holistic view of our administrative infrastructure. Our system for business process improvements is plagued by issues related to project prioritization, project management, implementation, transparency related to decision making, implementation issues resulting in local work-arounds, and training at roll-out that becomes outdated as modifications occur.

Executive Summary

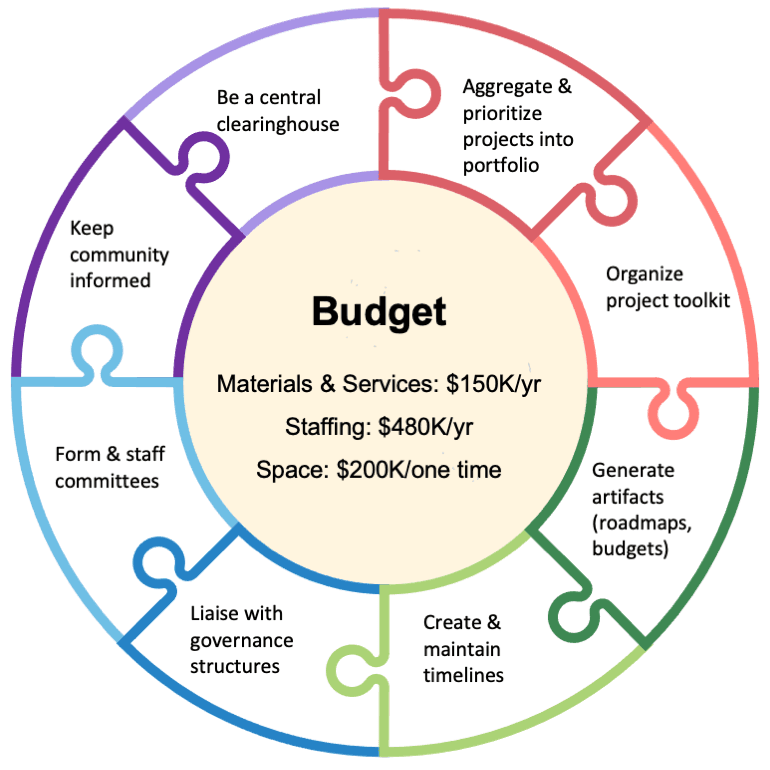

As charged by the Task Force 2021 Steering Committee, RIC 14 recommends the creation of the One Agile MIT Team, to shepherd strategic improvements to existing business processes and systems as well as providing support to new strategic initiatives. As the phase one Administrative Process team articulated, during a crisis, such as the world wide pandemic, MIT can act expeditiously to respond to unexpected organizational challenges. However, without the pressure of a crisis, MIT, like other organizations post-crisis, is unlikely to remain nimble and continue to make process and system improvements. The One Agile Team would mitigate the risk of future inaction by taking a more holistic view of the systems and processes at MIT through the creation of a cross-functional team that would coordinate projects and manage the portfolio of potential future projects and stakeholder input. This portfolio would be used to support senior leadership’s decision-making around administrative improvements. Projects could come from any area of the Institute and could be related to a process, a system, an initiative or a combination of these items as long as they are viewed as strategic priorities to senior leadership and stakeholders. However, not all projects will be immediately addressed to ensure that the portfolio remains small enough to ensure that prioritized projects can be completed successfully. The Team would also take responsibility for ensuring that the community understands where their pet projects are in the prioritization scheme or pipeline of active projects as well as provide them with opportunities to engage in improving our administrative infrastructure. The annual budget is estimated at $630K with an additional $200K during the first year to secure space, furnishings, and equipment. This budget does not include the costs associated with individual projects, which would be identified when the projects are scoped. We recommend that the body that oversees this office have a significant budget that can be deployed similarly to the mechanism used by the Committee on Space and Renovation Planning rather than tied to an annual budgeting process. As we emerge from the pandemic and an increasingly tight labor market as a result of employees' desire to remain remote, improving our antiquated administrative system and processes will be crucial to our ability to attract and retain staff members.

Background

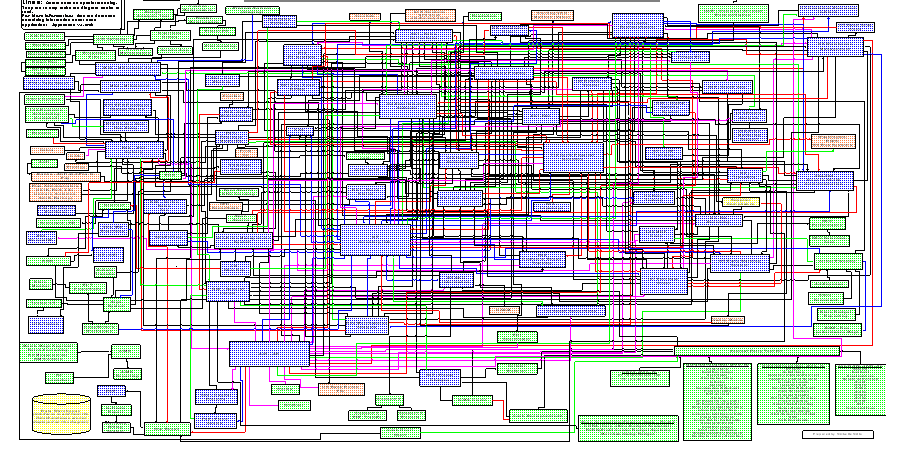

The landscape of higher education is growing in complexity. MIT’s funding portfolio continues to evolve with more complicated agreements and rules, our students and staff demand a more supportive environment, and teaching and learning paradigms are shifting. Yet, in these times that require flexibility and nimbleness, our business process and supporting systems are often antiquated. Many of our systems are heavily customized with stand-alone web-based work arounds created at both central and local units that, while functional, increases the number of steps required to process transactions or secure the data necessary for decision making (see image of our data architecture). As a result, much of our documentation is incomplete and outdated, and determining data lineage or impact is impossible. Learning our systems is possible. However, for new hires and individuals with expanded duties, our administrative structure is fraught with complexity and time intensive shadow systems. We now find that our ability to hire and retain staff members has diminished with competitors recruiting staff. On Glassdoor, the top five cons about working at MIT, includes, “Workload can be high at times… There were long hours… and Low pay, no structure in management”. As the June 9th Town Hall to discuss the return to campus made clear, many staff are frustrated with business as usual. As we and our competitors emerge from the pandemic, some of our competitors will seek to replace staff members who choose not to remain in the workforce, by recruiting our top administrators.

While we celebrate our agility during our transition to a largely remote workforce, we note that several of the successful administrative improvements that occurred during the pandemic, such as the use of Canvas, benefited from the efforts of Sloan and the Student Systems Steering Committee, only requiring senior leadership to commit the necessary resources to extend the Sloan implementation to the rest of campus. Similarly, Slack was already in use by many tech savvy administrators who were eager for MIT to invest in a site license. This increased the adoption and use of the program once the decision was made to invest the resources into an enterprise-wide solution. In comparison, many projects at MIT stall out for extended periods of time due to a handful of reasons, which we attribute to the following issues:

- Projects have poorly defined requirements, a lack of stakeholder identification, and unclear timelines which result in scope creep, delays that result in project fatigue, and in some cases, outcomes that do not meet the needs of key stakeholders (examples RAFT, Concur, Brio Query replacement).

- Distributive decision-making can hinder projects that require the coordination of multiple business owners (PI dashboard, underrecovery, forecasting system) and sometimes ignores projects that are pain points to the community (forecasting system, roles database, data integrity), which is likely the result of the lack a single business owner or champion.

- Limited financial and technical resources that lead to prioritizing critical maintenance of existing systems over long-term solutions that would result in higher quality new systems.

- Complex bureaucracy that impedes the transparency needed for projects to move forward, leading to competition among vocal stakeholders to influence the project portfolio and the project outcomes.

- A project staffing model that relies almost entirely on volunteers whose ability to lead and staff the project may become compromised when their primary MIT roles require their full attention.

- A highly political and competitive process for resource allocation that lacks any central set of priorities or coordination.

These challenges have a material impact on MIT. For example, a senior faculty member, when asked how much money he had in his accounts, proudly shared an excel document that listed all of his accounts, the account balances, and a few words in a notes column next to each account. He went on to explain that his administrative assistant generates the report for him each month and that she makes sure that she shows where each student is charged. He, and many others, are satisfied with a monthly summary of their account balances. Unfortunately, assuming that only 80% of our 1,067 faculty members have active research programs, and the administrative assistant spends just two hours per month creating the spreadsheet, the annual estimated cost to MIT is ~$686K. Given that this issue appeared as a concern in the 2008 Task Force report, we can assume that administrative assistants have been producing these reports for at least 14 years. As a result, a rough estimate of the amount that MIT has spent paying staff to generate these reports is ~$9.6M using today's rates. Ironically, in the consumer domain, nearly all major banks can provide account balances and transaction details on multiple devices with almost no lag in the availability of the data. MIT can do better.

Well-resourced units with staff members who have the technical skills to build a system that is easier to maintain do so. However, if the staff member who designs the system leaves MIT, the system collapses and any others who adopted the system are left without technical support. As a result of this, each unit does their own thing, and staff who transfer between units often must adapt to the local system. Regardless of the local system, in response to each request, a request requires that an administrator extract and verify the data, summarize the information into a simplified format, and return it to the faculty member via email. The faculty member, or their assistant, must then combine the information received from the administrator with other pieces of information to make the result useful.

Concept

One Agile MIT group will tackle these types of long-standing issues by mitigating the obstacles noted above by (1) drafting and owning a scatterplot of potential projects for senior leaders to prioritize; (2) generating road maps for projects that clearly define the resources (people and financial) and the decision making process; (3) forming and staffing committees to undertake the work approved by the stakeholders that leverages the expertise of team members without asking them to perform administrative support of the projects; (4) generating and maintaining adherence to timelines that include scheduled stakeholder sessions and dates that team members will be asked to confirm they can attend at the start of the project; (5) keeping the community informed; and (6) liaising with Information Technology Governance Committee (ITGC), the decision-making body for managing the Institute’s IT resources, and other leaders on a defined schedule.

The implementation plan as illustrated in the accompanying figure has four main components divided into eight distinct categories of activities (see the Appendix for a detailed summary of the implementation and the budget). At a high level, our recommendation is for two phases. During the first phase, a subset of the RIC 14 team will work with senior leadership (Provost, Chancellor, EVPT, etc.) to hire two full-time employees (FTEs) to be assigned to document our processes on a timeline, develop possible criteria for prioritization, work with senior leadership and stakeholders to vet the potential projects, develop a mechanism for revising the prioritization on a regular basis, and then create the process for moving projects through the system. During the second phase, projects will begin to move through the system. To successfully do so, the plan requires two additional FTEs to increase project management capacity and handle the extensive meeting logistics. The implementation also includes a request for dedicated space. During this phase, the One Agile Team will provide support to the project teams to allow expert stakeholders to participate in the project without being asked to undertake administrative duties. In the long-term, we hope that this office can act as a resource to projects across the Institute, convene local project managers, provide training and resources to the community on best practices, and provide opportunities for increased engagement by community members in defining the work for the future.

To be successful, the One Agile Team needs the support and commitment of senior leaders with respect to prioritization, ongoing decision-making, and resources (space, finance, and headcount). Although the One Agile Team efforts will result in the centralization of some projects, the path for many other projects is already clearly established through existing structures, such as IST, as well as within individual units. We note that, although some increased centralization is anticipated, we do not expect this Team to replace the people who develop local solutions or are early adopters of new resources. As noted above, these local efforts can grow into larger projects and eventually provide Institute-wide solutions to common challenges. We believe that One Agile MIT can both support a path for these decentralized innovations and provide opportunities for the larger community to engage as we improve MIT’s administrative structures and our community’s ability to make decisions and free up time for strategic planning.